Here we shall raise our children and be as little chickens under mother sheo's [Prairie hen's] wing. - from Black Elk Speaks

Here we shall raise our children and be as little chickens under mother sheo's [Prairie hen's] wing. - from Black Elk SpeaksThere has been a rash of scholarly books in recent years, like Cassandra here in Dr. Who, declaring the End Times (and millenialist spiritualist societies, like the Raelians above from an Economist article). In fact, it has become a small industry. As it is in the pop culture, the thinking man’s Mad Max or Bladerunner usually ascribes the imminent fall as a uniform failure throughout the entire culture, like the fall of the U.S.S.R. all at once, due to some virus that affects the entire body; liberalism, permissiveness or drugs.

The fairly recent of these is The Death of the West by conservative presidential candidate Pat Buchanon, presenting himself here as the working man’s Jacques Barzun. Spengler he ain’t, but his point is essentially the same as the mandarin-class fin de seicle scholars of the 1990s. This might be called a death archetype at work, and it has been apparent since the end of the Second World War. We always think we are going to die. There was a stock cartoon back in the 1950s in magazines like The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post which showed an itinerant non-denominational monk in beard and sandals walking down a street like

The fairly recent of these is The Death of the West by conservative presidential candidate Pat Buchanon, presenting himself here as the working man’s Jacques Barzun. Spengler he ain’t, but his point is essentially the same as the mandarin-class fin de seicle scholars of the 1990s. This might be called a death archetype at work, and it has been apparent since the end of the Second World War. We always think we are going to die. There was a stock cartoon back in the 1950s in magazines like The New Yorker and The Saturday Evening Post which showed an itinerant non-denominational monk in beard and sandals walking down a street like

It is a vague collective fear that something is dying. This is a vagueness that comes naturally to people, particularly those over 50, particularly men, so it should be cautioned that this could be a projection that death is being seen by one whose time is up or coming up, and he or she projects it onto the world around him. As comic Jackie Vernon once put it in one of his routines: he had an uncle who was always predicting that the world was coming to an end and for him it did.

people, particularly those over 50, particularly men, so it should be cautioned that this could be a projection that death is being seen by one whose time is up or coming up, and he or she projects it onto the world around him. As comic Jackie Vernon once put it in one of his routines: he had an uncle who was always predicting that the world was coming to an end and for him it did.

But that which weakens one faction of the culture often strengthens another. And for a public prognosticator, it is less than responsible to predict the End of Days and not say why or how or what is dying and what will follow. Where many of the public pronouncements are particularly lacking is in the what; that is, in identifying what groups, classes and specifically what cultures will be affected in the impending doom. WE’RE ALL GONNA DIE! Is the general trend. This is an inherently silly view of old men for whom it hasn’t gone as they’d liked the last 20 years of so. Everybody dies.

This is important because societies, like the human body, are made up of component parts that are interdependent on each other and with component parts that are dependant on universal systems of the body. If the heart dies, all systems collapse. But if the appendix fails, it can usually be safely removed, and it has lost its overall historical function anyway. Then again, if an arm or leg is lost it doesn’t mean the entire body will give up the ghost. The function can be mechanically replicated or it can be done without.

The human body is a good analogy for cultural failure but not a great one. A family is a better one: If a father dies he may be replaced by a daughter, which could bring fundamental change to the family culture, maybe positive change, but not necessarily destruction. And that analogy is limited as well, as the larger human society is infinitely more complex. But that one is better because in a human society, when one component dies it often allows life to flourish in other components. Particularly in a culture as young and healthy as the

is limited as well, as the larger human society is infinitely more complex. But that one is better because in a human society, when one component dies it often allows life to flourish in other components. Particularly in a culture as young and healthy as the

Often when a prognosticator sees death it is the death or the loss of function of his own particular class or social group. But death is a necessary ingredient for the long and continued life of the overall culture. When one force grows to strength it sends others into submission. And when the strong force dies, the submissive forces grow strong and flourish.

The classic novel and film Gone With the Wind illustrates. The film is often described as an account of an entire culture swept away by the Civil War. Very definitely a certain way of life was swept away and a certain class of people lost their function. The planter class, particularly those in

After the Civil War it was largely over for the English planter class. Some moved to New England and some back to

After the Civil War it was largely over for the English planter class. Some moved to New England and some back to

In terms of cultural death, the only thing that was really gone with the wind when the Southern independence movement yielded to Yankee federalism was the function of the Southern upper class. Its historical time had already passed before the war and when it finally lost its function it liberated new forces such as those of the poor-white – the so-called Scotch-Irish - and the blacks who were kept impoverished and enslaved under the previous system.

The overall death predicted by some public prognosticators doesn’t appear to be the death of the whole culture, but a change in the culture as a whole. This may seem like death to components that are yielding, but others feel like they are just coming to life.

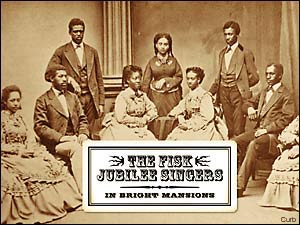

The black Pentecostal church, for example, is not dying in this milieu of ennui. Indeed, it glows and bringing health and strength to its churchgoers and to its regions, whether in rural

When we lived in the South, all our neighbors, both white and black, seem to have preserved a slight degree of healthy indifference to the rise and fall of the American condition and its globalist networks, in spite of the region’s overall acceptance of the Yankee management principles. The scholarly death cry comes from elsewhere. Perhaps because the South has found the amazing grace that accompanies utter failure; the seed of salvation that came with devastation in the Civil War. As C. Vann Woodward expressed it, “. . . Southern history, unlike American, includes large components of frustration, failure, and defeat. It includes not only an overwhelming military defeat but long decades of defeat in the provinces of economic, social, and political life. Such a heritage affords the Southern people no basis for delusion that there is nothing whatever that is beyond their power to accomplish.”

Southerners share this with the general run of mankind, Vann Woodward points out, but not with the rest of Americans.

No comments:

Post a Comment